What Is Religious Harm?

When faith causes trauma and lasting impact

Religious harm refers to the psychological, emotional, relational, and identity-level damage that can occur within religious or spiritual systems—especially those that rely on fear, control, shame, or rigid belief structures. It can affect people who remain religious, people who leave religion, and those still unsure what they believe. For many, the harm isn’t obvious at first—because it was intertwined with love, meaning, and belonging.

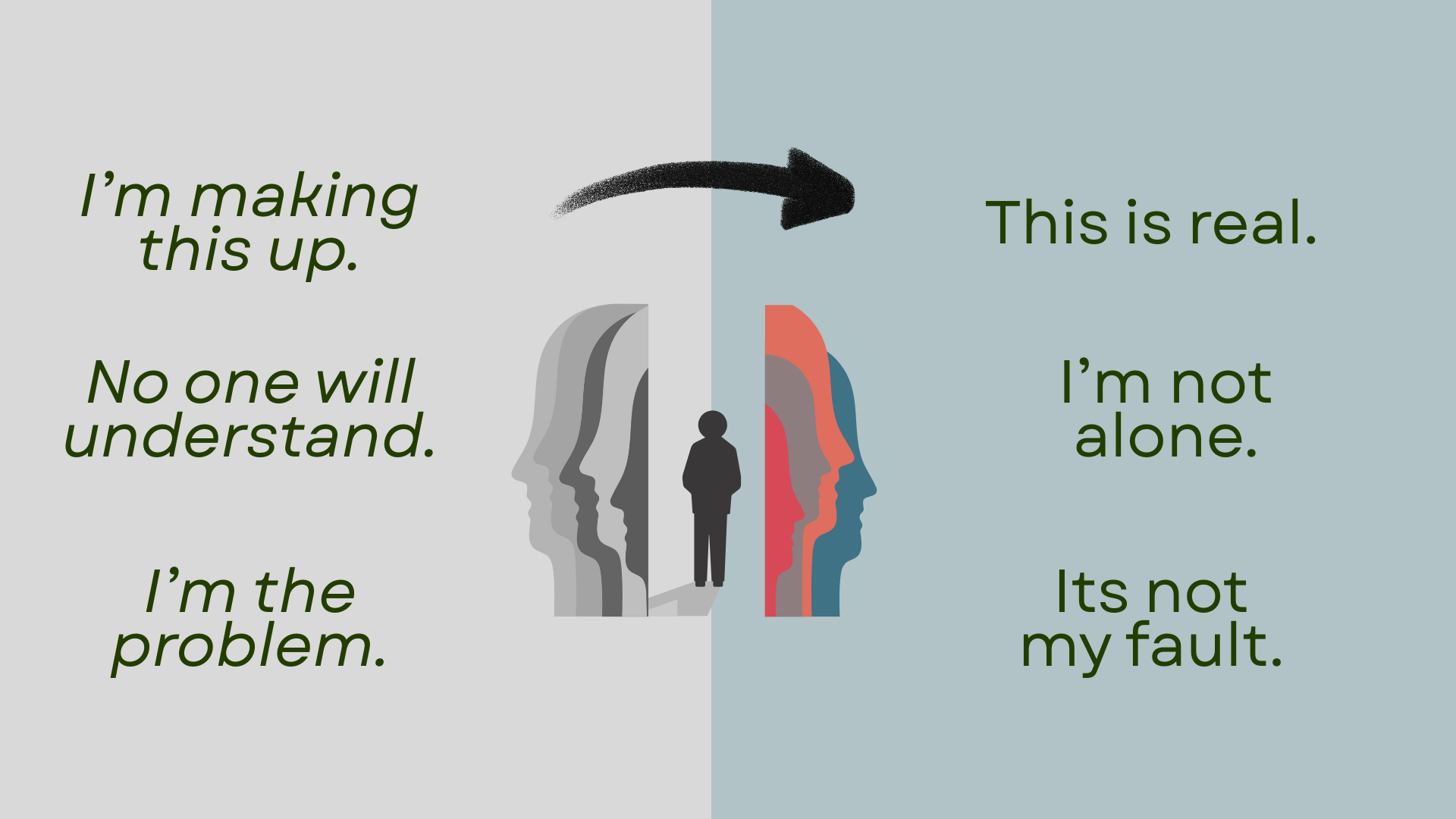

Many people experiencing religious harm question their own reality. Because harmful religious experiences are often normalized—or even praised—survivors may blame themselves, minimize their pain, or feel isolated.

Naming religious harm helps replace self-doubt with clarity, validation, and connection.

Types of Religious Harm

Religious harm can take many forms. Some experiences are overt, while others are subtle and cumulative.

Many people experience more than one type at the same time—especially in high-control or fear-based religious environments.

Why Religious Harm

Is Multi-Layered

Religion provides for core psychological needs which makes harm hard to unravel.

Mental-Health & Emotional Regulation

Religion often doubles as a mental-health toolkit. The meditative qualities of worship—singing, chanting, rhythmic breathing—can release endorphins and create a calming physiological effect. Sermons offer reflective space that encourages contemplation and reframing of stress. Prayer provides structure for processing emotions, expressing fears, and seeking comfort. Many religious teachings also give practical guidance for relationships, parenting, forgiveness, and conflict—offering a sense of stability and a roadmap for everyday life. For many, religion is the first and only experience of regulation and support for mental health needs.

Attachment

God is often an attachment figure who offers safety, unconditional love, guidance, and a secure base to return to when life feels frightening. Many people experience a relationship to a God as someone who sees them, understands them, and provides emotional protection. Community and spiritual leaders often function similarly as powerful attachment bonds.

Meaning-Making & Identity

Faith systems give people a framework for understanding life’s big questions. Why are we here? What happens when we die? These belief structures can function like an internal compass, providing comfort, coherence, and a sense of direction during uncertainty. Religion also gives a direct and prescriptive identity answer. It defines individual roles, life guidance, and shared narratives about purpose.

Community & Belonging

Religion offers built-in community, which is a foundational human need. Community offers connection, support, and reduces isolation. Community is a safety net for life’s difficult moments and a place to celebrate life’s major milestones. Religion creates predictable rhythms of gathering that help people stay connected and offers the complex organizational tools to coordinate large groups of people.

What Religion Provides

When Helping and

Harming CoExist

When the same system that offered emotional regulation, attachment security, meaning making, and belonging becomes a source of deep wounding, the ripple effects are immense. People are not just dealing with one aspect of their life—they are losing connection to many, if not most, of their basic needs.

Religious harm means attachment trauma, community abandonment, social shaming, the loss of meaning and identity, a lack of mental health tools among other things. This complexity makes religious harm uniquely painful to untangle.

Survivors must sort through a system that provided many needed things and created deep wounds at the same time.

This complexity is why healing from religious harm is not about simply “letting go” or “moving on”—it is about rebuilding safety, meaning, and trust at multiple levels.

Vulnerable Populations

While anyone can experience religious harm, certain populations face higher risk due to power imbalances, dependency, or systemic inequality within religious structures.

Children are particularly vulnerable in high-control religious settings, where cognitive development, autonomy, and consent are limited. Children are dependent on caregivers for safety and learning which layers on additional layers of complexity. Adults who were born into a high control religious group may have additional challenges in healing. if they were raised in the group from childhood due to the impact during formative years.

Individuals within the LGBTQIA+ community encounter heightened abuses in non-affirming religious settings compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers. Shame-based ideology and religious policies that selectively targets this community can lead to significant psychological and emotional distress.

Women face heightened vulnerability within religious communities that have patriarchal structures. The effects can be deeply damaging—eroding a woman’s sense of autonomy, self-worth, and personal agency. Strict gender roles that restrict education and career pursuits can stifle growth, independence, and economic security. Women are often more susceptible to various forms of abuse in religious settings where sexuality is partitioned behind shame and secrecy.

Racial prejudice is baked into the historical foundations of some religious communities. Racial minorities are further at risk of exploitation, harmful theologies, and racism disguised by religious rhetoric. Especially complicated are the examples where religion has offered minority groups a narrative of strength and resilience in the face of collective racial trauma. Pulling apart what was harmful and what was helpful can be confusing.