Recovering Beliefs

Coping with indoctrination while

rebuilding identity and meaning

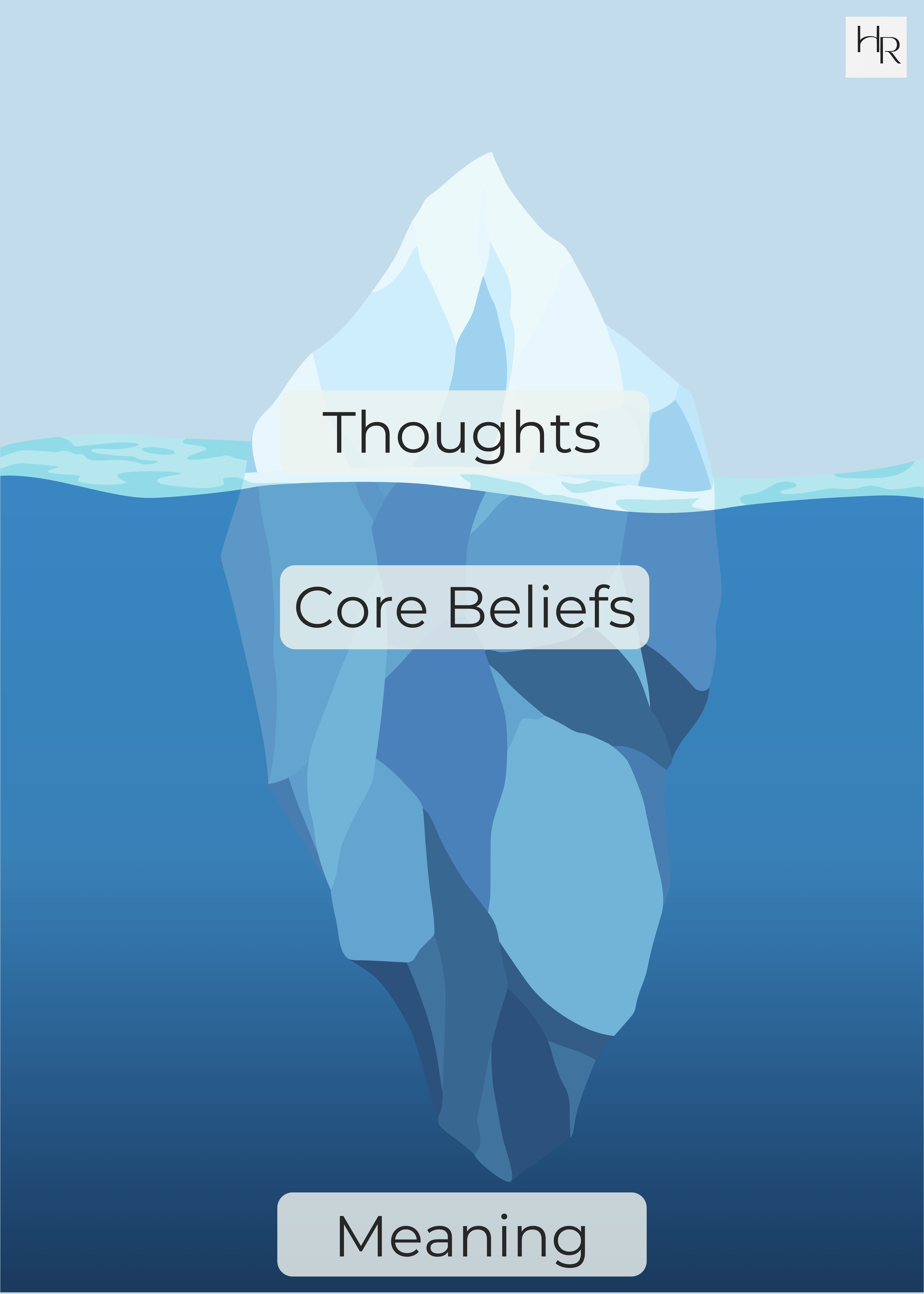

Healing from religion often involves multiple layers of belief, including our thinking patterns, core beliefs, and systems of meaning. At the surface level of awareness, intrusive thoughts can arise as old religious messages that pop up even after you no longer believe them. Beneath the conscious surface are core beliefs about who you are—beliefs shaped by early learning and emotional experience and often wired into the nervous system. At the deepest level is the meaning-making context you are floating in—the “ocean” of meaning that frames how you understand life, death, and the big why questions humans have grappled with for as long as we have existed. Rebuilding this orientation is essential for navigating life. This page explores all three layers, how they differ, and how healing can happen at each one.

Managing Old Religious Messages

It is very common for old religious narratives to continue showing up in a person’s thoughts—even after they have changed their beliefs, left a religion, or no longer agree with the ideas themselves. Sometimes these thoughts are unwanted visitors- in psychology we can these intrusive thoughts. even when the thoughts are unwanted. They may sound like a familiar verse, a religious song, teachings, or an internal dialogue that echoes what a former religious version of yourself might have said.

This is not a sign that something is wrong with you, nor does it mean you haven’t truly changed.

This experience is a normal part of how the brain stores, retrieves, and prioritizes information. Our brains give special weight to material that carries emotional intensity, perceived threats to safety, and frequent repetition. Deeply ingrained beliefs function like a well-traveled ten-lane highway—paths that have been reinforced over years of use. For those exposed to religious messages from childhood through songs, sermons, imagery, scripture, and constant community reinforcement, these neural pathways become especially strong. Even when you are consciously choosing a new direction, your brain may automatically route you back onto familiar roads.

The good news is that even deeply wired messages can change—but this process takes time and patience. In psychology, recurring unwanted thoughts are referred to as intrusive thoughts. One of the most important things to understand about them is this: the more a person tries to suppress, avoid, or forcibly stop these thoughts, the stronger and more frequent they often become.

There is neuroscience behind intrusive thoughts

Healing Intrusive Religious Thoughts

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), the goal is not to eliminate intrusive religious thoughts but to drop the struggle with them. When you fight, argue with, or try to suppress these thoughts, you often give them more power and attention which keeps them stuck. Instead, ACT teaches you to notice the thoughts as mental events—words, images, or sounds your mind produces—rather than truths that require action or debate. You might gently label them as “old religious programming” or “my indoctrinated mind doing its thing,” allowing them to come and go without engaging. By making space for these thoughts while redirecting your attention to what you care about in the present moment, you reduce their grip over time. The thoughts may still appear, but they no longer control your behavior, your values, or your sense of self.

Core Beliefs

Core beliefs are the deep, often unspoken conclusions we form about ourselves, other people, and the world. They develop early in life and act like a lens through which we interpret everything that happens to us. In high-control or fear-based religious environments, core beliefs are frequently shaped through shame, threat, and conditional acceptance. Over time, these messages can become internalized as “truths,” even long after a person no longer agrees with the religion itself.

Examples of harmful religious core beliefs might include:

I am bad, sinful, or broken.

I can’t trust myself.

I am only worthy if I obey or believe correctly.

I am not safe.

Although intrusive religious thoughts and harmful core beliefs can sound similar on the surface, they function differently in the mind and therefore require different kinds of healing. Intrusive thoughts are mental events—words, images, or phrases that pop into awareness automatically. They are often remnants of fear-based conditioning and do not necessarily reflect what you believe or value now. With intrusive thoughts, the thoughts may continue to appear, but they lose urgency, emotional charge, and behavioral control.

Success looks like: “The thought shows up, and I don’t have to do anything about it.”

Core beliefs are deep conclusions about who you are, how the world works, and what is required to be safe or worthy. They shape identity, expectations, and emotional responses—not just passing thoughts.

Core belief work often requires new emotional learning, not just insight.

This is where approaches like EMDR, somatic therapy, and relational repair are especially powerful because they allow the brain to reprocess stored experiences and update old conclusions at a deeper level.

While EMDR usually requires a trained therapist, people can begin core belief healing on their own through awareness, values-based living, compassionate parts work, and repeated experiences of safety and agency.

Success looks like: “This no longer feels true about who I am.”

Healing Core Beliefs

Healing core beliefs involves requires changing what the nervous system and meaning-making system expect to reprocess stored experiences and update old conclusions at a deeper level. Some approaches include somatic approaches, relational repair, and therapy work like EMDR.

Success looks like: “This no longer feels true about who I am.”

Corrective Relational Experiences

Relational repair plays a powerful role in healing core beliefs because many harmful beliefs were formed in relationships so they need to be healed in relationships.

Being believed, having boundaries honored, making mistakes without punishment, and expressing disagreement without threat all provide corrective emotional experiences that slowly rewire core beliefs at a deeper level than insight alone. Over time, these lived experiences send a new message: I am safe to be myself, I matter, and connection does not require self-erasure. This kind of repair can occur in multiple venues: therapy, friendships, support groups, or family relationships. It is often one of the most effective ways core beliefs shaped by harmful religion begin to truly change.

Healing Core Beliefs Held via the Body

Sometimes core beliefs are held by the body. For example, you see a religious trigger and your thoughts feel calm, but your pulse quickens, adrenaline spikes, breath gets held. Perhaps your body even physically shakes. The brain may be saying, “I’m fine.” but the body is screaming, “I am not safe.”

Healing beliefs held by the body means healing the nervous system. This process begins with recognizing the body’s cues, and building skills to tolerate nervous system dysregulation and eventually learning to cue the body into safety. Practices such as grounding, gentle movement, breath awareness, orienting to safety, and tracking sensations during emotional moments can help the body gently re orient to a felt sense of safety. Over time as the body regains safety, core beliefs shift from the bottom up.

Healing Core Beliefs in Therapy

Healing core beliefs in therapy involves creating a safe, consistent relationship where old beliefs can be gently brought into awareness and updated through new emotional experiences. A trained therapist helps identify the beliefs that were shaped by fear, shame, or control and supports the client in exploring where those beliefs came from and how they once served a protective purpose. Through approaches such as EMDR, parts work, cognitive and somatic therapies, clients are able to process past experiences in a way that allows the nervous system to release outdated conclusions about worth, safety, and identity. Over time, the therapeutic relationship itself becomes a powerful source of repair—offering attunement, validation, and choice—so that new, more compassionate beliefs can take root and begin to feel true, not just understood.

From an Internal Family Systems (IFS) perspective, intrusive religious thoughts can be understood as a younger part of you that is still carrying fear-based indoctrination and protective beliefs about safety. This part learned early on that remembering religious rules, warnings, or doctrines was necessary to avoid danger, punishment, or loss of love. When these thoughts show up, it isn’t because you are regressing—it’s because this younger part is trying to protect you the only way it knows how. Rather than pushing it away or arguing with it, IFS encourages you to turn toward this part with curiosity and compassion from your adult Self. You might gently acknowledge its fears, thank it for trying to keep you safe, and let it know that you are no longer in the same situation and can handle life now. Practices like writing a letter to this younger part, looking at a photo of yourself from the time you were indoctrinated, or working with a trained therapist can help this part feel seen and reassured. As the part begins to trust your adult Self, it often relaxes, and the intrusive thoughts lose their urgency and intensity.

Meaning Making

The Void

“Without a map, we wander.” — Jerome Bruner

One of the major benefits of religion is that it provides people a framework for understanding the BIG questions in life. What happens when we die? What is the meaning of life? Religion provides an automatic, prepackaged answer for most of those questions.

Humans are wired to orient ourselves to the world around us. Meaning making frameworks are tools for navigation- like maps. So when the map that you rely on to live is leading you in a wrong direction, or becomes dated- it creates a lot of distress. This is one big reason why the early part of recovery from religious harm is so challenging.

The “dark night of the soul” is a term often used to describe a period of deep disorientation and emotional pain that can occur when meaning making maps collapse. When an old framework falls away before a new one has formed, it is incredibly destabilizing. During this time of vulnerability people are more at risk of feelings of hopelessness, despair, anxiety, and other mental health challenges. There are ways of rebuilding new meaning and recovering from the existential crisis period. It happens slowly, often in small pieces- but it is possible.

Exploring New Ideas

Existential Therapy

Recovering Meaning

One of the perks of moving away from a restrictive religious perspective is that you get to explore—learning about other ways of viewing the world, ethics, and how to live can be fulfilling. There are many philosophies that do not include a religious premise, but still celebrate community, common narratives and values, etc. Books, clubs, and secular organization are great places to explore ideas.

Exploring new beliefs is also likely to bring challenges. It’s ok to explore other groups and ideas at a pace that feels good to you. Some people do not find it useful to explore other ideas or groups and focus on other aspects of life (hobbies, career, etc) altogether. Everyone is different.

Here are a few quick examples of other belief systems that you might find interesting:

Humanism

Meaning and ethics grounded in human wellbeing — learn more through the American Humanist Association’s resources.

Secular Buddhism

Practice-based approaches to suffering, attention, and compassion without requiring supernatural beliefs. Explore via Secular Buddhist Network or Secular Buddhist Tradition.

Naturalism and Ecocentrism

The natural world is enough; meaning can grow from nature, science, and care for the living world. Sees humans as part of an interconnected ecological system rather than separate from or above nature.

Pragmatism

Values ideas based on their usefulness and real-world impact rather than whether they are “ultimately true.”

Pluralism

Holds that many perspectives can coexist, and that no single framework has a monopoly on truth or meaning.

Stoicism

Focus on what you can control; practice steadiness and resilience

Existential Therapy addresses how people make meaning in the face of life’s fundamental uncertainties—such as freedom, responsibility, isolation, and death. Rather than offering new beliefs to replace old ones, it helps individuals grieving lost certainties, tolerating ambiguity without panic, and discovering meaning that feels self-authored rather than imposed. Through reflection, dialogue, and values-based exploration, clients learn that meaning does not have to be fixed or absolute to be sustaining, and that they can orient their lives with integrity even without final answers. If you want to learn more a few authors to explore are:

Irvin D. Yalom

Staring at the Sun (excellent for death anxiety)

Love’s Executioner (therapy stories that illuminate existential themes)

Vitor Frankl

Man’s Search for Meaning

James Bugental

The Search for Authenticity

Skills for Tolerating Uncertainty

When we find ourselves past the edges of the map that we thought we could rely on, and our navigational systems are down, we have to find new ways to tolerate uncertainty. One helpful tool is acceptance.

Radical acceptance is a concept of learning to tolerate things you cannot change- uncertainty is a part of life we cannot change. The following is a helpful guide for building up the skill of tolerating uncertainty with radical acceptance.